The Science of Fretboard Learning: Practical Insights for Guitarists

Knowing your fretboard from AR to traditional learning.

In this article, it should be understood that I am considering learning the fretboard differently from sight reading. Here, learning the fretboard means knowing the notes of the fretboard itself and not translating from the page to the instrument.

If you’ve ever tried to memorize the guitar fretboard and felt like you were drowning in a sea of notes, patterns, and fingerings, you’re not alone. Learning the fretboard is notoriously overwhelming, especially for beginners. And while we guitarists have no shortage of opinions on the “best” way to learn it, the truth is—when it comes to peer-reviewed research specifically focused on fretboard learning—there’s surprisingly little out there.

Still, a small but growing body of research gives us some insight into what might actually make fretboard learning more efficient. One of the clearer takeaways is that how we learn physically—through our bodies—matters just as much as what we’re trying to learn. Studies in embodied music cognition emphasize the role of the body’s sensorimotor system, suggesting that perception, action, and cognition are all closely tied together through physical interaction with the instrument (Keebler, 2014).

This becomes especially relevant when we consider how traditional learning tools like sheet music or tablature function. These require learners to go through a “transformational process”—essentially translating external symbols into physical action on the guitar, which can slow things down and create a cognitive barrier (Marky, 2021). When musical information is provided directly on the instrument, rather than on an external page, that translation step is reduced or even eliminated, allowing students to focus fully on playing. The result is a more embodied engagement with the instrument and a noticeable reduction in cognitive load (Keebler, 2014).

This is where smart guitars and augmented reality systems come into play. Tools like the Fretlight® guitar, which uses embedded LED lights to illuminate notes on the fretboard, have been studied with interesting results. Research has shown that Fretlight helps beginners get started more easily and perform faster in early learning stages. Users showed better long-term retention of scales, made fewer mistakes during training, and kept a more consistent quality of scale execution over time (Keebler, 2014).

Another system, Let’s Frets, combines visual LED indicators with capacitive sensors that capture finger position. LEDs alone help learners realize new finger placements quickly and intuitively. Still, when combined with position-tracking (LED-CS), the system supports more accurate playing and reduces errors, especially helpful for beginners. It’s also flexible. Beginners benefit from the visual cues, while more advanced students can use the system for analyzing technique or even composing. Importantly, these systems are designed to integrate seamlessly into the guitar without disrupting how it feels to play (Marky, 2021).

Of course, even promising technologies have their limitations. Some learners found that traditional fretboard charts felt more realistic when transitioning to standard performance settings (Marky, 2021). Others raised questions about how useful LED systems are for more complex material, like seven-note scales, compared to pentatonics (Keebler, 2014). And from a design standpoint, some prototypes still have physical drawbacks—exposed wires or lack of feedback from strummed strings—that may be distracting or limiting, especially for more experienced players (Marky, 2021).

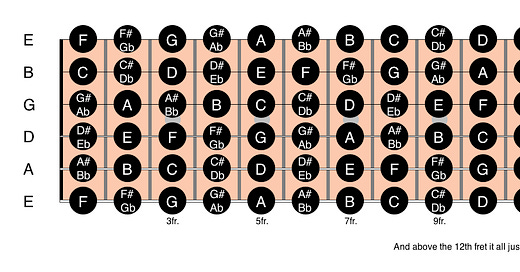

While technology can offer a leg up, learning the fretboard efficiently also depends on how we visualize and move across it. Unlike many instruments, the guitar allows the same pitch to appear in multiple places. This means a single phrase might have several fretboard “solutions,” and part of learning the fretboard is understanding and experimenting with these pathways. How a player travels from one note to another—what kind of “route” they take—can shape their sense of style and even lead to more personal, original forms of musical expression (Dean, 2023).

To support this kind of exploration, several visualization systems have been developed over time. One approach is unitar playing—focusing on a single string to connect spatial movement directly with interval distance. This strengthens note recognition and interval awareness without relying on boxed finger patterns. Another approach is learning chords and scales as muscle-memorized "finger routes" or grips, which become automatic through repetition (Dean, 2023).

Then there’s the widely used CAGED system, which connects chord shapes and scale patterns across the fretboard. By understanding how different chord forms fit together, learners can build a comprehensive mental map of scale and melodic possibilities that extend out from familiar chord shapes. Intervallic thinking offers yet another lens, starting from a reference note, the fretboard can be viewed in terms of distance relationships between notes, helping players move fluidly and assertively (Dean, 2023).

Some teachers and learners also break the fretboard into smaller, manageable "chunks" or “cells,” often covering a span of four frets. This kind of spatial compartmentalization can helpfully limit choices, paradoxically creating more creative freedom by breaking reliance on habitual patterns (Dean, 2023). Others look for geometric patterns—triangles, rectangles, squares—that repeat in chord forms and scale shapes. Studies have shown that many guitarists, especially visual learners, naturally organize their fretboard understanding using these shapes (Baah-Duodu, 2025).

Even with these modern tools and strategies, the role of the teacher remains essential. While AR and smart guitars can lower the barrier for beginners, traditional classical methods are still the most commonly used in actual teaching settings. Teachers provide much more than information—they guide hand position, correct posture, clarify rhythm, and help shape musical expression. They also catch the small, hard-to-notice errors that students often miss, making their feedback invaluable (Gómez-Ullate, 2019).

Interestingly, some research suggests that while smart systems can boost confidence and motivation, they often inspire students to seek out more traditional instruction once they feel capable enough to move forward (Keebler, 2014). As one study summed it up, it’s “still hard to learn, especially without a guitar teacher” (Gómez-Ullate, 2019).

So, where does that leave us? Efficient fretboard learning is likely best approached through a combination of tools. Technologies that reduce mental strain and provide immediate, physical feedback can accelerate early progress. Visualization strategies like CAGED or intervallic thinking help form a roadmap for long-term growth. And along the way, guidance from a good teacher ties it all together, providing context, correction, and musical depth that no software can replicate.

If the fretboard still feels like a maze, that’s okay. But with the right mix of smart tools, thoughtful strategies, and a teacher, you will find that the fretboard maze starts to look more like a map.

Sources:

Samuel Baah-Duodu, “Geometric Analysis of Fret-Board Patterns and Navigation: Exploring Mathematical Structures in Guitar Music,” Akenten Appiah-Menka University of Skills Training and Entrepreneurial Development (2024).

James Dean, “Fretboard navigation strategies in jazz guitar improvisation: theory and practice,” (PhD. diss., University of Surrey, 2023).

Martin Gómez-Ullate, “Guitar Teaching: State Of The Art And Research Questions,” Society. Integration. Education (2019), 4: 361-357.

Joseph R. Keebler, Travis J. Wiltshire, Dustin C. Smith, Stephen M. Fiore, & Jeffrey S. Bedwell, “Shifting the paradigm of music instruction: Implications of embodiment stemming from an augmented reality guitar learning system,” Frontiers in Psychology (2014), 5.

Karola Marky, Andreas Weiß, Andrii Matviienko, Sabastian Wolf, Martin Schmitz, Florian Ktrell, Florian Müller, & Max Mühlhäuser, “Let’s Frets! Assisting Guitar Students During Practice via Capacitive Sensing,” CHI (2021).